-

About brain injury

-

For individuals

- Types of brain injury

-

Effects of brain injury

- Behavioural effects of brain injury

- Cognitive effects of brain injury

- Coma and reduced awareness states

- Communication problems

- Emotional effects of brain injury

- Executive dysfunction

- Fatigue after brain injury

- Hormonal imbalances

- Memory problems

- Physical effects of brain injury

- Post-traumatic amnesia

- Hospital treatment and early recovery

- Rehabilitation and continuing care

- Practical issues

- Relationships after brain injury

- Caring

- Information library

- Free training for brain injury survivors

-

Brain injury and me

- "But you don't look disabled"

- Shana Lewis

- Robert Ashton

- Laura Bailey 2015

- Jane Allberry

- Michaela

- Ian Litchfield

- Debi Pullen

- David Thomas

- Alison Winterburn

- Mel Lightfoot

- Annette Henry

- Denise Johnson

- Codey Sharp

- Keith Emmanuel

- Lizzie Smart

- Gwen and Natalie Milham

- Terisha Burge

- Maria Knights

- Joanne Davis

- Sarah Whitchurch

- Amy Perring

- Jane Clarke

- Peter Holmes

- Luke Flavell

- Lindsay Lapham

- Pip Taylor

- Nic O'Leary

- Angus Swanson

- Tom Birch

- Samuel Bishop

- Phil Broxton

- Nell Gregory

- Jamie Gailer

- Kate and John Bosley

- Gary Winters

- Kathryn Edgington

- Charlie and Jake Korving

- Bruno Muratori

- Kerry Jeffs

- Mike McCall

- James Piercy

- Andy Nicholson

- Warren McKinlay

- Lauren and Claire Cowlishaw

- Sarah McKinlay

- David Horner

- Arthur Moore

- Mike Palmer

- Sarah Tomlinson

- Paul Leyland

- Tina Young

- Warwick Jarvis

- Jackie and John Mills

- Adrian Ellis

- Kieran Wallis

- Eleanor Simcox

- Jack Rutter

- Jan Luxton

- Daniel Lingard

- Bernie Bambury

- Lorraine and Kevin Pratt

- Paul Pugh

- Melanie Whittaker

- Naomi

- John Holbrook

- Tom Wright

- Jackie Alton

- Irvine Phair

- Rebecca Grant

- Rachel Atkinson

- Marco Gambi

- Brenda and Julian

- Callum Maclean

- A simple solution

- Lost in a crowd

- Caring for carers

- Dear my new brain

- Holiday from brain injury

- The new me and my Jumbledbrain blog

- The old me is not the new me

- I see Headway as the pit stop

- Riding my horse Johnny keeps me focused

- Headway is a haven

- Brain injury didn't steal my future

- Never give up

- Anna Khan

- Fiona Grant-MacDonald

- Kiran Higgins

- Jetting off alone

- Dad 2.0

- Dislabeled

- Matt Brammeier

- Syreeta

- Brain injury vs family

- The Face of Brain Injury With Dee Snider

- Mourning lost relationships

- A mother's perspective

- Pathological laughter - it's no joke

- HiddenInMe

- Polly Williamson

- Writing a book after brain injury

- Michael Mabon

- Jeff Mayle

- A day in the life of a carer

- "Kerry the HATS nurse was my guardian angel"

- Don't struggle alone

- Harriet Barnsley

- I don't want anyone to feel as alone as I did

- Amanda Horton

- Jeff Clare

- A helping hand

- Donnie McHarg

- Shona Green

- Jenny Joppa

- Philippa Taylor

- Debra Jones

- John Dougan

- "No memory of the day that changed my life"

- Nick Gibbs

- Jean Parker

- My experience of parenting after brain injury

- Sue McIntyre

- Daniel Mole

- Keely McGhee

- Paula Stanford

- Relationships after brain injury – Imogen’s story

- Jules Pring

- Tara Moore

- Dr Amy Izycky's Headway Exhibition

- Nicola Brown

- Rod Maxwell

- Joy Webb

- Grace Vobe

- Doing it the Head way

- Carer vacancy. Unpaid. Full time. No experience required.

- Joe Sandford

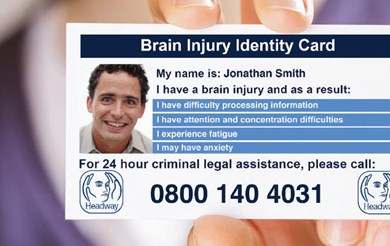

- My Brain Injury ID Card

- Matthew Nichols

- Heather Pollard

- Danielle

- Noelle Robinson

- Giles Hudson

- Q&A - ‘Be in the moment. This is all you have.’

- Q&A – “I would be the Happiness Fairy, I’ve sprinkled Happy Dust on you, now smile.”

- Nature's Way: Gardening after brain injury

- The debilitating impact of social isolation

- Joanne Wood - Who

- David Greer

- Lynne O'Grady

- Clair Bennett

- Danielle's story - returning home

- Anne Johnston

- Q&A: Cat

- How I overcame panic attacks

- Q&A with Zalehka Price-Davies

- Philippa-Anne Dewhirst

- After my brain injury I kept questioning, 'what if I have lost my ability to be creative?'

- Chris Bryant

- Busting the myths around brain injury and sex

- I swear, he knew he was helping me

- Hannah Brandon

- Keith Poultney

- Joanna Darmody

- Terry Slade

- Tamara Bond

- Kavita Basi

- Nigel Limb

- Learning to live again

- David Wheeler

- Jessica Stevens

- Andrew Plowright

- Steve Borland

- Tracey Cox

- Financial fraud: a risk you can't afford to ignore

- Dating after brain injury

- Max Muteliso

- Q&A: Roger Merriman

- Parenting with a brain injury

- Ben Clench

- Kieran Broadfield

- Max Munro

- Louise Lane

- Adam Nicke - Q&A

- Hitting the High Street at Headway's Hinckley shop

- Hitting the high street at headway hinckley

- London Marathon Runners

- Rebecca Hutchings

- Joanne Wood

- Paws for Thought

- Jake Elliott

- Growing Together with Headway Cambridgeshire

- Lauren Walkington Q&A

- Daniel Parslow

- Alex Murphy

- Matt Masson

- Alphabet Brains

- Pete Bourne

- David Yabbacome

- Julie Sadler

- Lottie Butler

- Candice Ridley

- Belinda Medlock

- Unravelling the mystery of fatigue

- Lara Newson: Head Smash

- Robert Courtnell

- Hipatia Preis

- Stewart Gray

- Mary's Story

- Hannah O'Dowd

- Victoria Wicks

- Carol Smith

- ABI Week across the UK

- Rebecca Ivatts

- Nicola Evans

- 'Writing gives me meaning'

- The perils of gambling after brain injury

- Fit for purpose: The benefits of being active after brain injury

- Festival fun after brain injury

- 6 strategies for getting back to work after brain injury

- Matt Rhodes

- Clare Hull

- Stop the bus! A guide to public transport

- Maria Munn

- Brain injury: To tell or not to tell?

- 5 ways to cope with taste and smell problems after brain injury

- The uneasy relationship between alcohol and brain injury

- 9 ways to help with planning problems after brain injury

- 7 top tips for managing visual problems after brain injury

- 10 ways to cope with depression after brain injury

- Supporting children: visiting a parent in hospital

- Supporting children after a parent's brain injury: when a parent comes home

- Donna Siggers

- How to manage memory problems after brain injury

- Hot weather after brain injury: tips for keeping cool

- Stefan Leader

- Keith

- A picture speaks a thousand words

- Andrew Purnell

- Ruth Berkoff

- Sam Hulse

- Katherine McKinstry

- Chloé Briffa

- Socialising after brain injury

- Shane Booth

- Theme parks: accessibility after brain injury

- William Windle

- Ron Gains

- Rebecca Jones

- Sarah Scott

- Pregnancy after brain injury

- Music after brain injury

- Emma Martins

- Dancing after brain injury

- Scottie Elliott

- Let's talk tech

- Lorna Lancaster

- Carol Evans

- John Wrathall

- Fiona Baker-Holden

- Ryan Goodenough

- Christmas after brain injury

- Cecilia Danielsson

- Rik Waddon

- Saturday Night Fever

- Anthony Hewson

- Q&A: Julian Earl

- Fireworks after brain injury

- Coping with Christmas in hospital

- Eleanor Brander

- Beccy Young

- Veronica Woods

- 10 things not to say to someone with a brain injury

- Tracey Newman

- Lauren Gilligan

- Louis McGuire

- Fighting the bear

- David Macdonald

- Yvette Lumley

- Christina Sweeney

- Charlotte Warhurst

- Cindy Hollingsworth

- Spencer Senior

- Q&A: Steven Kelly

- Sarah Lane

- I am a firm believer in not just speaking of the change, but actively searching to be part of it.

- Carwyn Wooldridge

- Liz Wilson

- Lucy Rogoff

- Bryony Wilshaw

- David Wozny

- Sarah Allwood

- Leah Moore

- "We're all going on an assisted holiday"

- Anne's top tips for self-isolation

- Sammy's top tips for managing mental health problems during self-isolation

- Kavita's tips for self-isolation

- Belinda’s story: Isolation after brain injury

- Mikey Smithson

- Lucie Bell

- Let’s talk continence problems after brain injury

- Mark Kennedy

- Gary Younge

- Mindfulness and me

- Life in lockdown: Alison's story

- John Beaumont

- Catherine Erdal

- CinderZ

- Lyndsey Anderson

- Rock painting by Deborah Johnston

- Q&A: Hollie-Blue Huntsman

- Donna Davies

- Caroline Spiers

- Phil Birch

- More than my brain injury: Danielle Grant

- Brain Injury Sunblock and the Infernal Birdsong

- Sandra Liddell

- Brain Injury And Covid: Jane Hallard

- Brain Injury And Covid: Jean Parker

- A day in the life of a Headway helpline consultant

- Brain injury and Covid: Tom Harris

- Brain Injury And Covid: Michael Perry

- Rebekah Nesbitt

- The Headway helpline: You're not alone

- The price of a punch

- David Baker

- Donna Harris

- 7 signs of executive dysfunction after brain injury

- My poetry: Joseph McAloon

- Angela Lewis

- Daniel Sutherland

- Andrew Brown

- Sarah McGrath

- Dan Goldstraw

- In her own words: Emma Davey

- My poetry: John Marshall

- Disinfectant by Sarah-Louise Lennon

- Karen Whitehead

- Wendy Joss

- In his own words: Max Bongard

- Karl Hargreaves

- Animation: Memory loss after brain injury

- How to cope with memory problems after brain injury

- Q&A: George Mitchell

- Michelle Hay

- Q&A: Alan Heal

- Lucy Hunter

- Cara's story

- Q&A: Rosemary Shaw

- Mental health and brain injury

- Emma Chivers

- Q&A: Terence Berritt

- Q&A: Emma Linnell

- Tai Chi After Brain Injury with Dr Giles Yeates

- In her own words: Emma Lindsay

- Phillip Cragg

- Paintings by Hannah Jenkins

- Q&A: Alison Rockall

- Imogen Cauthery

- Alex Danson-Bennett MBE

- My poetry: Helen Wilson

- Haydn Garrod

- Podcast: Life with no filter

- Overcoming challenges after brain injury

- Creative Expression: Mark and Jules Kennedy

- Eleanor Furneaux

- Creative Expression: Lucy Pugh

- Claire Bullimore

- My artwork: Sandra E Ball

- Blue Mundane Monday Mix by Glen Stephenson

- Nicola Cross

- Survival is a Team Dream by Philippa Bateman

- Brain Attack Music by Andy Dovey

- Top tips for coping with parenting through lockdown

- Pauline O'Connor

- Duncan Boak

- Gill and Terry Oliver

- Jelly Brain documentary: A gift to mum

- In her own words: Jodie Bacon

- Monica Petrosino

- Josh Rawson

- What triggers anger after brain injury?

- Gerald Heffernan

- Back behind the wheel: Paula Barlow

- Back behind the wheel: Driving FAQs

- Elizabeth Wilkins

- My poetry: Sam Norris

- Alex Richardson

- Emerging from lockdown: Tips for brain injury survivors

- My podcast by Nikki Webber MBE

- Isolation and loneliness: Life with no filter podcast

- A life of lockdown? Belinda's story

- A life of lockdown? Derek's story

- A life of lockdown? Melanie's story

- A life of lockdown? Elizabeth's story

- Mindfulness Training after Brain Injury with Dr Niels Detert

- Fresh Start by the Headway Glasgow Writing Group

- 'I've Made It!' by Becki York

- Lucy O'Donovan

- Top tips for coping with headaches

- Helena Breslin

- Sue Williams

- Reflections of Chair-Man Eason

- Ceara's story

- Tracy Dickson

- Julie Mueller

- Thomas Leeds

- Headaches: The whats, whys and hows

- My photography: Rob Dinwoodie

- Nick Henderson

- Lenka Brunclikova

- Emma Doherty

- Planting a seed of thought - Natalie Parr

- 'My Broken Brain' by Sam Hedges

- Sally Smith

- Catherine Jessop - Pulling Through

- Helen Bray

- Exploring your dreams

- Sweet dreams? Getting a good night's sleep after brain injury

- Mindfulness after brain injury

- Mike Clark

- Amy Streather

- Eleanor May Blackburn

- Paul Wilkins

- Barry Cusack: My body and mind

- Our relationship reality: Love after brain injury

- Love after brain injury: Thalia and Matt

- Tisha's story

- Executive dysfunction explained

- Let’s talk about sex...

- When Catwalks are Barbed

- Hope by Angela Webb

- Dee Gall

- Headway gets creative!

- From a child's mind to centre stage

- Bernadette Bendall

- Zoe Rainaki

- What did you not see? By Stef Harvey

- A Windy Moment by Nick Fletcher

- Helen and Liz

- The Sound of Recovery

- A family united to support life after brain injury

- See the Hidden Me: Iona's story

- See the Hidden Me: Annette's story

- See the Hidden Me: John's story

- See the Hidden Me: Christine's story

- The Brain Injury Cookbook

- Raj Gataora

- Marco Gambi: A passion for food

- Celebrating 10,000 Brain Injury ID Cards

- 'Rehabilitation rather than incarceration'

- Theresa Malcom

- Tim Richens

- Visual problems: A closer look

- Dusty Zeisberger – 24-hour treadmill challenge

- A conversation with... Ian Scott-Logan

- Ways to help cope at Christmas: tips for survivors, families, friends, and carers

- Lisa

- Bryce Bell

- World’s first ABI Games a huge success!

- Steven Lomas

- Memory systems

- Stevie Ward

- Five Years On by Clare Jones

- The Penny Drops

- Stephen Evans

- Don’t get bitten by the sharks!

- Jonathan Hirons

- Finding your superpower...

- Post-traumatic growth after brain injury

- Nick Blackwell

- Heads, Hats and Healing: Making and Creating Silver Linings

- Nigel and Paula's story

- Joseph's story

- John's story

- How to manage isolation after brain injury

- Managing anxiety after brain injury

- Simon and Marc's story

- Sandi's story

- Relearning life skills

- "A charity of love"

- Dawn, Headway volunteer

- Pat Griffiths, Chair of Trustees for Headway Meirionnydd

- Creative writing sessions: Laura Bailey

- Creative writing sessions: Helen Davies

- Nicola Bird Blunt

- In her own words: Lynn Boyle

- My brother was killed by one punch: Aaron Matcham

- Completing my life-long dream of running the Brighton Marathon: Adam Clarke

- 8 ways to manage a lack of insight after brain injury

- How to help someone with a brain injury: Top tips for friends and family

- Balance problems after brain injury

- Safe travels! Your holiday tips

- Early warning signs of fatigue

- Keeping your relationship healthy after brain injury

- Carers: Try these 4 ways to care for yourself

- 7 tips for volunteering after brain injury

- 10 top tips for coping with stress after brain injury

- Top 10 tips for staying safe online

- In memory of much-loved partner and dad

- 10 ways to manage anger: tips for brain injury survivors

- Managing impulsivity and disinhibition following brain injury

- Friends: 5 ways to support someone with a brain injury

- Diet after brain injury: Healthy body, healthy mind?

- Top tips for a good night's sleep

- An awfully big row: Giles Johnson

- Jurate Ardour

- Dean Osborne

- Errol

- Iain Millar: Rising from Adversity to Find Purpose on the Golf Course

- Finding Hope on the Fairway, Anthony Roberts' Journey of Resilience and Inspiration

- Ben Fowler

- James Heather

- Andy Southey

- From one punch victim to Headway Hero: A Half Marathon triumph

- Mark Winterbourne

- World Mental Health Day

- Thanking Our Fundraiser: Sahara Trek Triumphm

- Sisters’ challenge inspired by ‘hero’ sibling’s brain injury

- Ed Dunford

- The devastating consequences of one punch

- Get to know – Jen, Director of Fundraising

- Putting the ‘I’ in identity after brain injury

- Coping with winter blues

- Making returning to work, work for you

- Alan's story

- Get to know – Sarah, Trust and Foundations Manager

- Give up, or focus tremendously on rehabilitation

- What really counts?

- Laura Macfarlane

- The role art can play in positive change

- World Poetry Day

- Poem: TBI Survivor

- Adapting to life after brain injury: Returning to work

- Meet the volunteer - Roger Beattie

- We are family! Siblings run for Headway in support of their mum

- The impact of brain injury on a family

- A craniotomy – ‘the last resort’

- David's story A Life Re-written

- Andrew's story A Life Re-written

- Alison's story A Life Re-written

- Liz and Justina's story A Life Re-written

- Amnesia and identity

- Belfast Marathon

- Don't ignore the warning signs

- Dr Roger Weddell

- Helen Shaw – Headway South Cumbria

- Trevor Hall – Headway Hartlepool

- Alan McKnight - Finaghy volunteer

- A company-wide charity day in aid of Headway

- My pain monster

- Inspirational brain injury advocate Dr. Bruce Powell Joins Headway Charity Golf Day

- The Aphasia Theatre Group

- Caolan McCormick

- Liam Hamilton

- Let's go on holiday!

- Lasting Power of Attorney

- Peter's 3D model

- Headaches after brain injury: tips for Pain Awareness Month

- A journey from brain injury to the golf course with Headway

- Headway Cardiff's 1920s-inspired silent movie

- Author and brain tumour survivor has over 475,000 Facebook followers

- UK-based award-winning insurance company, Hastings Direct, steps forward for Headway

- Georgina's story

- Shopping without the stress after brain injury

- Connecting with nature after brain injury

- Martin’s Journey: Overcoming Intracranial Subdural Empyema

- Drained by fatigue? Try these 8 ways to cope after brain injury

- Menopause after brain injury

- Hosting or attending an event

- Elle's story: Life beyond post-concussion

- Steve Lightly

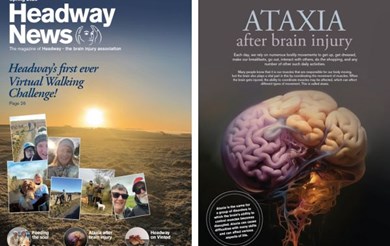

- Ataxia after brain injury

- The benefits of singing for brain injury survivors

- Concussion, head impacts and brain blood vessel function Q&A

- 10 reasons why you should join Eden's team in the Great North Swim

- Being seen and accepted after brain injury

- The Waiting Room a short film created by Headway Newtonabbey

- Q&A with Amarachi Nwaneri

-

For professionals

- Approved Provider scheme

- Criminal Justice System Professionals

- Events and conferences

- GPs

- Headway Head Injury Solicitors Directory

- Headway services

-

Headway webinars

-

Webinar recordings

- Life after acquired brain injury: Coping with anxiety and depression

- Smell and taste disorders after brain injury

- Fatigue after brain injury

- Managing sleep and fatigue after brain injury

- Nature’s benefit after brain injury

- Brain Injury in the Criminal justice System

- Managing memory problems after brain injury

- Identity change after brain injury

- Headway’s 2023 policy and public affairs round-up

- Disability discrimination in the workplace

- Understanding and responding to behaviours that challenge following acquired brain injury

- Moving towards digital care

- Mind the Gap: Navigating Social Care after Acquired brain Injury

- Covid and the brain: what we know so far

- Addiction and brain injury

- De-mystifying mental capacity

- Returning to work after brain injury

- Diet and nutrition after brain injury

- Head Injury and the Criminal Justice System in Scotland

- Understanding Personality Change After Brain Injury

- Post-traumatic Stress Disorder After Brain Injury

- Brain Blood Flow Regulation After Brain Injury

- Mental Health and Brain Injury

- Experiences and Challenges Faced by Family Members after Brain Injury

- Frontal Lobe Problems After Brain Injury

- Emotional Lability Following Brain Injury

-

Webinar recordings

-

Training courses

- Understanding MY brain injury

- Navigating life after brain injury

- An introduction to brain injury

- Understanding brain injury

- Effective communication strategies

- Understanding behaviours that challenge

- Goals setting training

- Brain Injury Solicitors training

- Understanding brain injury training for criminal justice professionals

- Headway group training sessions

- Further information

-

Featured

-

Stories of life after brain injury

Stories of life after brain injury

-

-

For individuals

-

Supporting you test

-

Supporting you

- In your area

- Helpline

- Brain Injury Identity Card

- Headway Emergency Fund

- Headway’s Justice Programme

- Online communities

- Keeping family and friends updated

- I recently sustained a brain injury

- I'm living with a brain injury

- Someone I know has a brain injury

-

Featured

-

Get support near you

Get support near you -

Legal advice

Legal advice -

Brain Injury Identity Card

Brain Injury Identity Card

-

-

Supporting you

-

News and campaigns

- News and stories

- Campaigns

-

Featured

-

Headway News spring 2025

Headway News spring 2025 -

Budget for brain injury

Budget for brain injury

-

-

Get involved

-

Fundraise for us

- Hats for Headway Day

- Headway Charity Golf Day

- Virtual fundraising: Facebook Challenge

-

Take on a challenge

- Find your local event

-

Run, swim, cycle

- Amsterdam Half Marathon

- Barcelona Marathon

- Bath Half Marathon

- Brighton Marathon

- Cardiff Half Marathon

- Dorney Lakes Duathlon

- Edinburgh Marathon Festival

- Great Manchester Run 10K

- Great Manchester Run Half Marathon

- London 10k

- Great North Run Half Marathon

- Great North Swim Quiet Wave

- Great Scottish Run 10K

- Great Scottish Run Half Marathon

- Hackney Half Marathon

- London Landmarks Half Marathon

- London to Paris cycle ride

- Manchester Half Marathon

- Manchester Marathon

- Paris Half Marathon

- Paris Marathon

- Royal Parks Half Marathon

- TCS London Marathon

- Tough Mudder

- Ultra Challenge Series

- World famous marathons with realbuzz

- Yorkshire Marathon

- Treks and walks

- Skydives

- Corporate events

- Bungee jumps

- Friends of Headway

- Payroll Giving

- Organising your own event?

- Download your fundraising pack

- Easy ways to support us

- Headway Annual Awards

- Organisations

- Donate

- Volunteer with us

-

Fundraise for us

-

My story

- Brain injury and me

-

Featured

-

Brain injury and me

Brain injury and me -

Simon and Marc's story

Simon and Marc's story -

Nigel and Paula's story

Nigel and Paula's story

-

-

About Headway

-

Our organisation

-

Events and conferences

- Headway webinar series

- Headway training courses

- Hats for Headway Day

- Action for Brain Injury (ABI) Week

- Volunteers' Week

- Carers Week: Caring About Equality

- Hard Hat Awareness Week

- Headway Charity Golf Day

- Second Hand September

- Mince Pie Morning

- Headway Annual Awards

- Look Ahead in the North

- ABI Games 2025

- Neuroplasticity in Action conference 2025

- Aims and objectives

- The history of Headway

- Contact us

- Accounts

-

Events and conferences

- Working with us

- Shop with us

-

Featured

-

Help us continue our work

Help us continue our work

-

-

Our organisation